Reptile Road Trip

Visiting museums, hospitals, traditional healers and community members to learn about Kenya's snakebite reality

Off to Baringo!

Back in the city, I met Robert Rono, a clinician and one of Kenya’s leading snakebite experts. Over Ethiopian coffee, he told me about his accidental initiation into the snakebite world. Baringo county, where Dr. Rono works, faces many venomous snakebites. However, people consider snakebite as more of an act of God rather than a public health crisis. Despite the poor access to snakebite care, no one seemed to be challenging the status quo.

A few news stories and research projects later, Dr. Rono realized that snakebite deaths were avoidable. He began implementing various policies across the county to improve hospital access and treatment quality at healthcare facilities. After some discussion, we gecided to head to Baringo county together. There, we would meet with one of Mary’s friends, Jamlick Lepaa. Lepaa is a biology student who was using his free time and pocket money to visit communities and teach them about snakes and snakebite first aid. After speaking over the phone, I was inspired by his commitment to community wellbeing and biodiversity and had to meet him. So, I spoke to Dr. Rono and asked if I could invite Lepaa. Thus, the awesome snakebite roadtrip was born.

Dr. Rono and I left Nairobi in the morning, picking up Lepaa for a Kenyan-Indian lunch of pilau rice. We shared stories and planned the coming days. We arrived to Kabernet, the capital of Baringo county, in the evening. At a cafe, we relaxed over tea. Lepaa made a few calls; he had worked in Baringo county for years, visiting elementary schools and communities to teach about snakes. He had a few ideas of people and places to visit, and was organizing meetings with them. Dr. Rono’s colleague, a pharmacist, joined us and began to describe the grim snakebite situation in Baringo.

A harsh reality

“Doctors don’t know whether snakebites are venomous or not. If it’s a snakebite, we administer one vial of antivenom no matter what,” the pharmacist shrugged. I was shocked. What about the risk of allergic reaction? The waste of scarce antivenom?

“They don’t do the 20 minute whole blood clotting test?” I asked, referring to a simple diagnostic measure that doctors use to test whether hemotoxicity occurred. They take a sample of blood into a clean test tube and let it sit for 20 minutes. If the blood coagulates, the patient is fine. If the blood is still runny, there are coagulation issues and the patient should be treated with antivenom.

Dr. Rono explained. “A lot of these small hospitals and health centers don’t even have test tubes. They don’t have access to labs to run tests, so they don’t buy tubes. Even if they know about the 20WBCT, many centers couldn’t do it.”

Many healthcare providers were too afraid to administer antivenom in the first place, due to a history of dangerous and ineffective products that used to circulate around the African continent. I was horrified. One vial of antivenom is an underdose for most Kenyan snakes; no antivenom therapy is a recipe for death and disability. We split ways and headed off to sleep, everyone’s minds churning about the information we shared.

Baringo County Hospital

The next morning, we visited the local hospital to discuss epidemiology and antivenom distribution. In Kenya, each county has its own system for pharaceutical distribution. Public sectors get antivenoms through KEMSA, occasionally turning to charity or private pharmacies in case of stock-outs. This is how some non-approved products get into the market; gaps in antivenom availability mean that doctors, patients and their families have to look anywhere and everywhere to find a replacement. Whether they find an effective or useless product is often a wildcard.

Museum

After visiting the hospital, we went to a local museum and reptile center. After touring the cultural exhibits, we collided with a small group of students who were visiting the museum. Gently, Lepaa began pointing at the snakes and sharing little tidbits of information in Swahili. He asked the children questions, and they smiled bashfully, responding. I watched as Lepaa captivated the students (and museum guide) with snakes and snakebite knowledge.

At the end of the exhibit, the museum guide admitted that she didn’t know much about snakes or snakebites, and wished she could learn more information to share with visitors. Lepaa and Dr. Rono made a plan to come back and train the museum staff on snakes and snakebite first aid, so that they could pass this knowledge on to others.

Community Stories

From the museum, we headed toward a family house close to Kabarnet. Walking down the driveway, I could feel the sweltering heat radiating from the read dirt. A goat bleated meekly in the background. Even the wind was hot and dry.

“This is the kind of weather that makes snakes look for water in people’s houses,” explained Lepaa. “It’s snakebite season.”

The family had set up a semi-circle of chairs around a table, and an adolescent boy sat at one. We greeted some family members and sat down, and Lepaa began speaking in Swahili with the boy. He had been bitten on the leg while in school, and his family took on medical debt for his care. For many months, they had scraped together documents and spent hours at police offices to try and get compensation. They didn’t know, however, that Kenya no longer covered snakebite victims’ medical costs.

In the past, the Kenyan Wildlife Service compensated victims of almost all human-wildlife conflicts, including snakebites, attacks by lions, hippos, cheetas, hyenas and other wild animals. However, snakebite cases flooded the system and drained the public coffers. Some crafty people even tried to fake snakebites to get compensation. Due to high number or snakebeite cases (and/ or frequent falsifications), the Kenyan Wildlife Service stopped compensating victims. Still, many people are unaware of the current rules surrounding the issue. Like this family, many may be missing work in vain, trying to get their medical debt covered.

We had to be the bearers of bad news, but Dr. Rono was able to give some medical advice. During the conversation, the family provided a warm lunch of beans and rice, with water and sweet juice. I was touched by their hospitality, and frustrated that I had nothing else to offer besides condolences.

Hospital Care: In Safe Hands?

That afternoon, we visited Marigat hospital, a medium sized hospital which recieves many snakebites. We spoke to nurse Bultut, who told us a bit about the history of snakebite treatment at Marigat.

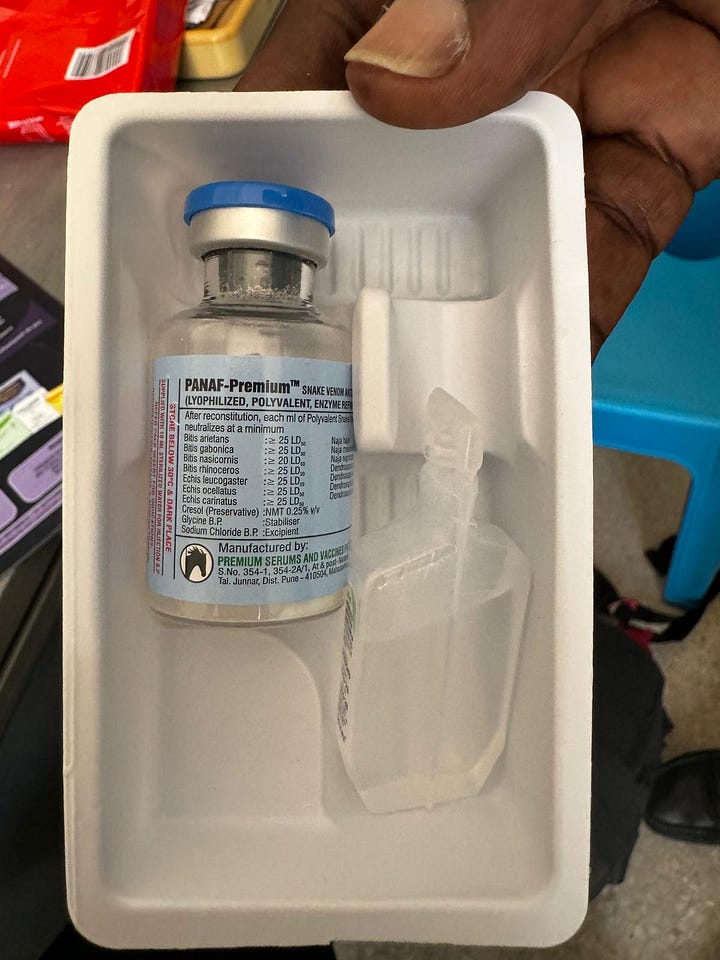

In the past, none of the hospital staff knew how to treat snakbites. With the help of Dr. Rono, an antivenom company, Premium Serums, conducted post market surveys in Baringo country to assess the safety and effectiveness of their African antivenom, PANAF-Premium. As part of thier visit, they trained healthcare providers at the Marigat hospital on clinical snakebite management. Now, the staff are much more confident in treating venomous snakebites. Mr. Bultut even makes videos for the hospital staff, explaining what to do in case of a snakebite envenoming.

While many training programs focus on doctors, front line healthcare providers are often nurses and pharmacists. In the case of snakebite, an urgent medical emergency, there’s often not enough time for victims to reach major hospitals. This experience in Kenya reinforced my persective that a doctor-centric snakebite strategy misses out on the practical reality.

That night, Dr. Rono, Lepaa and I had a Kenyan chapati dinner and talked about culture, life and snakebites. We discussed the day’s events, gradually weaving together potential plans for action.

Baringo Snake Park

The following morning, we headed toward a prominent local reptile park. Besides providing a place for children and adults to see local species, Lepaa explained that the park also provides venom for Kenyan Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) who are also working to make a local Kenyan antivenom.

We stepped out of the sun into the building; at first I thought it was abandoned. A smiling, aged man appeared out of the back of the quiet building, greeting Lepaa warmly. He showed us around the snake exhibits, letting us hold the sleepy sand boa.

They had a few specimens of each species, and many of the snakes looked tired or sick. Some Kenyan species were not present. Comparing the collection to K-SRIC or the Watamu snake farm, I was a bit surprised that this was KEMRI’s elected venom source.

After chatting with the staff, Lepaa turned to me.

“They’re not trained on snake handling or snakebite first aid. They would really like this knowledge, and they need it,” he explained.

Dr. Rono pitched in, “We should come back and do a training for them, as well as the museums. You can teach about snakes, and I’ll teach first aid.”

Lepaa and Dr. Rono exchanged ideas with the director, emphasizing the importance of such safety procedures.

Traditional Medicine

After saying our farewells, we went to visit a traditional healer. She was seated on a mat on the ground, surrounded by friends and family members. We shook hands with everyone, then sat down to talk.

Lepaa began asking her about her work, translating her asnwers to me. In fact, she wasn’t a traditional healer for all maladies; only snakebite, scorpion sting and spider bites. She treated these using a “black stone”. This stone, usually made using charred bones, is considered the best cure for snakebite.

“How many patients have you treated with the black stone?” we asked the healer.

“Thousands,” she responded.

“What is the procedure when someone shows up with a snakebite?”

“I cut the skin right where the fang marks were, opening up the wound. Then, I would place the stone. If it sticks, the snakebite was venomous. The stone then sucks out the venom and falls off when its done.”

Scientifically, it’s very difficult (see: basically impossible) to suck venom out once its in the blood. Some Indian friends used to describe it this way: imagine you pour milk in your coffee, then try to suck out only the milk. You can’t reverse the mixing, so any sucking of snakebites is usually useless (and dangerous, since you increase local circulation and risk giving an infection if you use your mouth).

However, many communities across India and Africa swear by black stones. The tradition originated in India hundreds or thousands of years ago, and has since spread far. Some say that this is due to the high prevalence of non-venomous and dry snakebites. Patients may use black stones and think that they have saved their lives, while there was never any venom to begin with.

“After the black stone treatment, I send patients to the hospital to get a tetanus shot,” the healer continued. Dr. Rono, Lepaa and I exchanged glances, shocked. Animal bite victims are recommended to get tetanus shots, whether venom was injected or not, due to the risk of contamination with the tetanus bacteria. It was surprising that she collaborated with local biomedical hospitals, and that she was aware of this medical indication.

“The hospital also refers patients to me,” she said, matter of factly.

“What are the patients’ symptoms like when they arrive?” I asked the healer through Lepaa’s translation.

“Swelling and pain,” she reponded.

“Any serious nosebleeds, bleeding from the bite, or decaying flesh? Do they ever arrive paralyzed?”

The women thought for a moment. “No, nothing like that. Mostly just swelling.”

Hmmm it sounds like she recieves mostly non-venomous and mildly venomous snakebites. I thought to myself. I wonder if patients seek her help for mild cases and go to the hospital for more severe cases?

The healer doesn’t collect any specific sum from patients. Instead, she lets them pay however they can and want. After an interesting conversation, we shook hands again and left.

The end of a Journey

After an incredible journey, Dr. Rono, Lepaa and I parted ways with ideas for future action. Lepaa and Dr. Rono discussed plans to repeat the trip, conducting training programs for schools, museums, snake parks and communities at each stop.

I think its safe to say that we all left feeling inspired, with new allies to take action against snakebite deaths in the future.

Want to learn more? Check out these links!

Baringo County Snakebite, article by Doctors Without Borders

Study of the efficacy of the black stone on envenomation

Breaking the Cycle of Neglect: Confronting Snakebite Envenoming in Kenya