The Ophirex Voyage, Part 1: Snake Walk and Clinical Trials

At the Oxford conference, Rabin and I had the fortune to meet Dr. Stephen Samuel, a medical doctor who works as Senior Vice President of Ophirex, and leader of Clinical Research & Medical Affairs in India. Ophirex is a private company (with public-benefit) that is working to create a field treatment for snakebite envenoming. Snake venom is made up of a plethora of complex cocktail of different toxins, proteins and peptides. Most severe symptoms of envenoming, however, are caused by four main toxin “families”:

Phospholipase A2s (sPLA2’s)

3 finger toxins (3-FT’s)

Snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMP’s)

Snake venom serine proteinases (SVSPs)

Ophirex’s candidate molecule, Varespladib, blocks sPLA2 toxins, which are found in at least 95% of venomous snake species globally. These toxins affect the nervous system, cause blood coagulation issues, and cell damage leading to tissue death. In short, sPLA2s are HEAVY HITTERS.

Oftentimes, snakebite victims are bitten in remote places, and have to travel hours to reach a hospital for antivenom treatment. The amazing thing about Varespladib is that it can be taken as a pill in the field. The new antidote is currently in phase 2 clinical trials in India, and Dr. Stephen invited us to join their trip!

I was sitting at the Crocodile Bank, registering for the GRE when Gnanewar turned up; he was just getting back from Harare, Zimbabwe, where some investors are considering opening up a new serpentarium and venom construction facility. He gave me a brief rundown of the situation before Dr. Stephen arrived from the UK with Jeremy Gowler, the new CEO of Ophirex. Gnanewar grabbed a lollipop and we all met at the front gate.

We walked Jeremy and Stephen around the park, pointing out the different crocodiles, including Thor, the huge croc who one time broke a cement wall, just to show off. After the tour around the Zoo, we headed to a seafood restaurant in Mahabalipuram. With the soft sounds of the ocean lapping the shore in the background, the waiter showed us an array of fresh, shiny fish, and scooped some live lobsters out of a tank. Stephen and Gnaneswar spoke with the waiter while Jeremy and I stared in awe at the fish. After a sumptuous and tangy seafood dinner (where I tried my first lobster), we all went home early; the following morning we would meet for an early morning snake walk with the Irular.

We met outside the Madras Crocodile Bank at 6:15am to drive out to the field. Gnaneswar overslept and came running out in a panic, equipped with a t-shirt, shorts and crocs. We drove out to meet Kali and Alamelu, an Irular couple who catch snakes as a team. They led us to an expansive farm, with flooded rice paddies and long grass, with small enclaves of trees scattered across the field. Flocks of birds dotted the morning skyline, and we trekked behind Kali and Alamelu.

An hour passed, then two. We spotted bird nests and medicinal plants, watching as the Irular couple scrutinized crevices and overturned rocks. Jeremy, Stephen, Gnaneswar and I chatted all the while about Ophirex’ plans for the next few years. Suddenly, Gnaneswar pointed at a wiggling flash in the grass; a skink! We tried to follow it as it weaved itself into the beige grass, then Gnaneswar spotted another gem. He lunged, and came up with a small snake with a tan belly and darker brown bands across its back. A striped keelback!

He carefully handed us the snake, and it wriggled through my fingers. I’m pretty scared of snakes, but I’ve been having so much exposure therapy that I’m developing an appreciation for their beauty. I would even say this one is cute!

After a few fruitless attempts to dig up kraits, Kali found a Giant Forest Scorpion; the world’s largest species of scorpion! This specimen had dozens of pale babies on its back. We ogled the scorpion for a few minutes before Kali covered its partially demolished home with a rock, for some privacy and protection from the sun.

We wrapped up the walk after three hours, spotting one last rat snake on the walk back. Kali and Alamelu nabbed the big yellow snake out of a bush, and Gnaneswar warned to be careful while handling these; they can be stinky! Jeremy was the first to hold the wriggling reptile, and it pooped itself in fear. Then, he passed it to me. The rat snake promptly wrapped itself around me, smearing its feces all over my arm and leg.

“Let go, let go!” Gnaneswar said. In panic and disgust, I put the snake onto the ground and it slithered back into the bush.

“Nooo, not like that. I meant to stop squeezing it,” he laughed.

Too late, the snake had disappeared and we were sweating in the humid heat of the day. We jumped back in the car and had a local breakfast. We stuffed poor Jeremy with idli (the soft, fluffy rice cakes), dosa (a buttery rice-based pancake), vada (a savory fried donut) and a variety of chutneys.

Following breakfast, we drove by an elementary school where the Croc Bank’s Snakebite Mitigation Project had sponsored an informational wall painting, describing basic first aid for snakebite envenoming. We dropped Jeremy and Dr. Stephen off to rest for a few hours, then reconnected in the afternoon to walk on the beach and have dinner.

The following morning, Stephen, Jeremy and I were heading to Pondicherry. There, they were running clinical trials for Varespladib at a famous public teaching hospital, JIPMER. Gnaneswar bid us farewell early morning, and we started the drive. I chatted with Stephen about his clinical experience and his journey to snakebite, and his experience organizing these trials in India.

The first round of Ophirex’s clinical trials, called BRAVO (Broad-spectrum Rapid Antidote: Varespladib Oral for snakebite), were only administered orally. These took place in both the US and India. Presently, Ophirex is running a second round of clinical trials, a project called BRAVIO (Broad-spectrum Rapid Antidote: Varespladib IV to Oral Trial for Snakebite). Many krait and cobra bite victims reach the hospital in a severe state of envenoming, so they are often unable to swallow. While hospital physicians can force the pills down in clinically safe ways, this second round of trials begins Varespladib administration intravenously, then switches to oral ingestion (hence the name).

On the way to Pondicherry lies a small experimental township called Auroville. This community describes itself as a “universal town where men and women of all countries are able to live in peace and progressive harmony above all creeds, all politics and nationalities… to realize human unity.” The 3,300 person township has an internal economy, its own visa process, and goals to eliminate or suppress the use of currency.

We stopped to explore the township and see the characteristic big golden globe, called the Matrimandir inside of which people meditate. Outside the main center, people sold food, coffee, baked goods and artisanal products. We meandered through the visitors center, which featured posters with smiling European women and children, and the occasional elderly Indian sages. Beside these, universalist creeds like “diversity” and “international understanding” had blurbs of information on the township’s history, values and projects. It was a sweltering walk, but a peaceful one, surrounded by greenery and an extensive network of “walking” banyan tree(s), with shooting trunks extending from branches to the ground.

After our visit and a quick coffee break, we completed the drive to Pondicherry, a union territory two hours south of Chennai that used to be a French colony. After a quick nap break (during which I did some studying for the GRE), we met up and headed to a ship-themed microbrewery, where we would be meeting Rabin (my colleague form the Madras Croc Bank) and the Principal Investigator (PI) in charge of the BRAVIO study at the JIPMER hospital. We walked up the stairs to the room, where raunchy bass-boosted 2010’s club music blasted, and a projector played music videos on the wall. The loud music was hard to talk over, so we just bobbed our heads, waiting for Rabin and the PI. Stephen ordered a flight of different beers for everyone to try, and Jeremy and I sipped and discussed over the music.

Once Rabin and the PI, arrived, we moved upstairs to the terrace, where softer music was playing and a cool breeze eased the sweltering heat of the day. Rabin had just come back from a visit to the US, where he reconnected with friends and family before returning to his field research. Our group ordered a pizza, some drinks, and a biryani, and discussed the trial. The PI was exhausted from a long day of work, Rabin from his travels, and the rest of us from our sunny day of tourism, so we turned in and agreed to meet in the morning at the hospital.

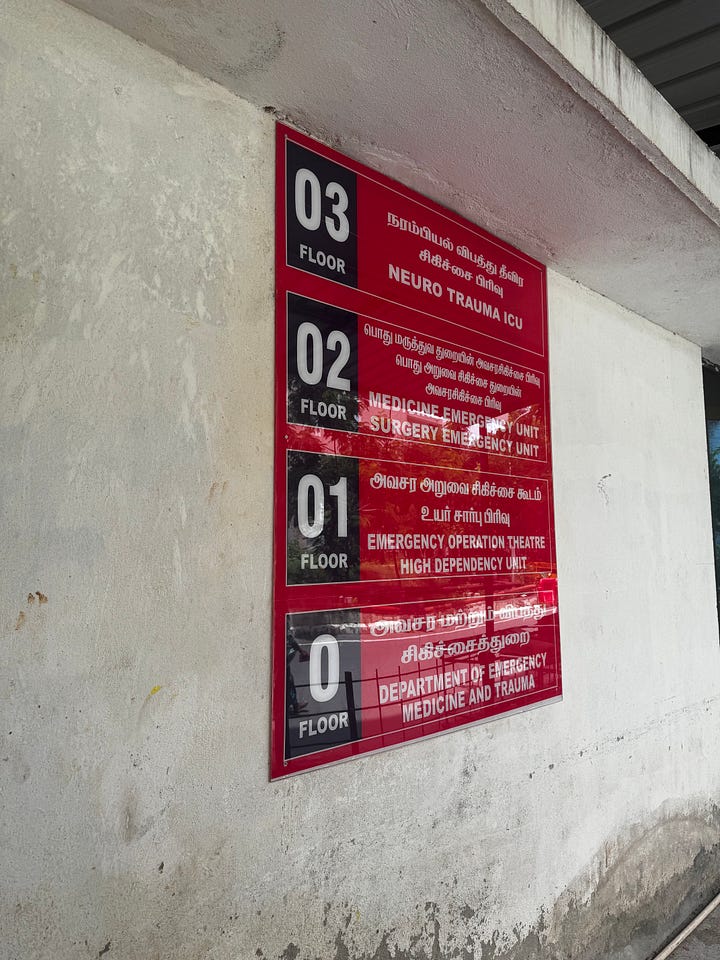

The next day, the PI showed us around the hospital, explaining their triage system, different care rooms and the double-blinded clinical trial procedures. The hospital has constant high traffic, since it offers excellent care free of charge. The PI answered our lingering questions, we shared a coffee and bid our farewells.

The following day, we visited the JIPMER hospital again to see a suspected krait bite patient. The older women had no visible symptoms, and had arrived at the hospital within an hour of the accident. “If she develops symptoms, it will take some time,” Dr. Stephen explained. The first signs of krait bites are droopy eyelids, and most cases develop abdominal pain. Dr. Stephen spoke to the patient, checking her abdomen for any early signs of envenoming. Luckily, nothing. Her sons and family members waited anxiously at the foot of her bed, and our presence seemed to worry the family (who did not speak English). We stepped out of the ICU to give the patients, clinicians and families some space, and headed to a cafe.

We ate a leisurely lunch, and after a few hours, got a call from JIPMER that the patient had still not developed any symptoms of envenoming. The staff would watch her for the next 24 hours, then let her go back home. So-called “dry bites,” where snakes strike without injecting venom are common. The venom is metabolically expensive (it takes a lot of energy) to produce, so snakes may give warning strikes, but save their venom for use in prey. Researchers have estimated that some venomous species only inject venom 50% of the time.

After lunch, we walked around on the beach and enjoyed a dinner at the hotel with the investigators involved in the BRAVIO trials. We would leave the following morning toward Krishnagiri, a town four hours to the north-west of Pondicherry, to visit a famous private snakebite specialty hospital. Stay tuned for the second half of this trip!

Want to learn more? Check out these links!

BRAVO Study