Venom in Vietnam

Phở-Nomenal work being done to address snakebites in this Southeast Asian country. Oh, and I ate a snake (sorry)!

Getting Settled

My flight landed in Hanoi toward the evening. At the baggage claim, I met a group of fellow travelers from around the world. We shared a taxi toward the old city, where all of our hostels were. Outside the window, the evening cityscape bustled with bright lights, hawkers, tourists, and busy locals. There seemed to be no traffic laws, as motorcyclists in green jackets weaved through traffic and pedestrians cut across the narrow roads at every opportunity. I was surprised our taxi had made it so far.

Our young crew said our farewells and each went our separate ways, exchanging information. I had booked the “Mad Monkey” hostel (which I found is a party hostel). I checked in and dropped my bags, then went to fill my water bottle downstairs.

The first floor of the hotel was a bar. A group of men surrounded me as I waited for the bartender to fill my plastic bottle. In American, Australian, and Indian accents, they bombarded me with questions and invited me to join the Mad Monkey pub crawl. Tired and hungry, I politely declined. I wished them a fun night before stepping out to grab a banh mi and explore the city.

Sandwich in hand, I waded through the crowd, dodging drunk bar-goers and speeding motorcycles. The neon lights of restaurant signage and bodegas contrasted sharply with ornate Vietnamese architecture of stone temples, somehow right next door to one another. I was soaking up the night life from outside.

The sound of live music drew me down a crowded alley, lined with open air bars. Tables dotted the overcrowded pathway, further slowing the stream of movement. A live rock band played in one, sounds mixing with electronic music blaring from the neighboring bar. Vietnamese ladies in danced energetically on the table, and bar waiters beckoned me, offering free shots. In another bar, scantily clad young men swung around a pole. I hastened my pace back toward my hotel, feeling both amused and bashful.

Tourism Time

I slept deeply, and woke up to explore Hanoi. The old city looked quite different in the cool air of the morning. Old men sat sipping coffee and noodles at tables on the street. Motorcycles zipped around street puddles. Women carried a long pole over their shoulder, balancing two large baskets of fruits or vegetables on each end.

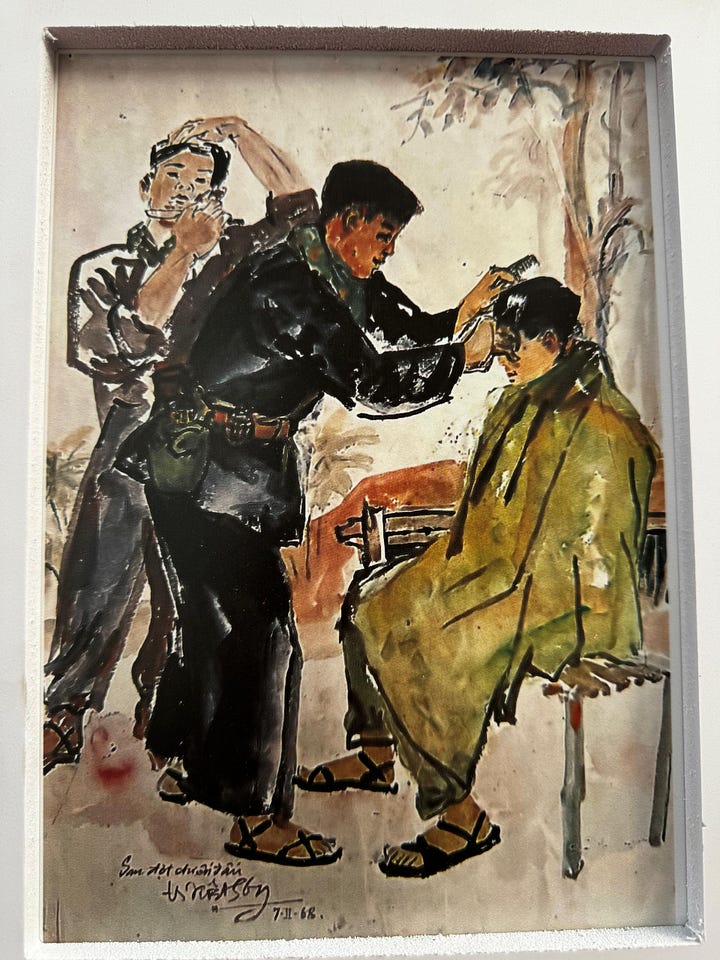

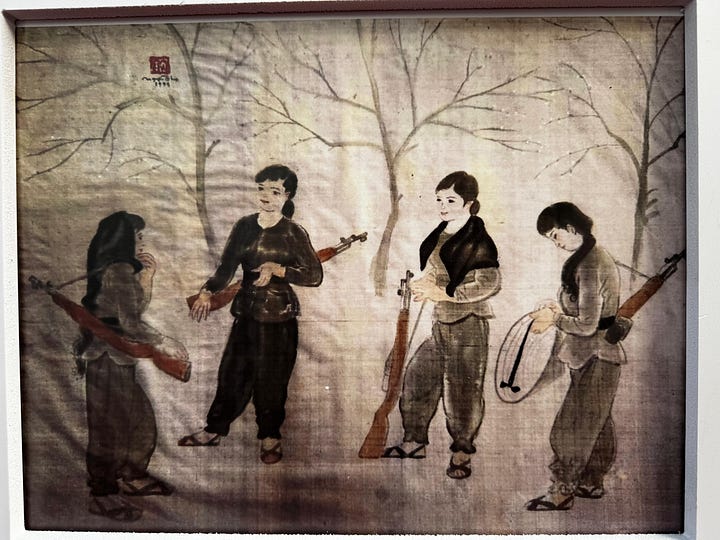

I grabbed an egg coffee, a sweet, creamy and rich coffee with egg yolks, sugar, espresso and condensed milk, then explored a temple of knowledge in the middle of a lake. Upon exiting, a fleet of Vietnamese army men marched past me, in neat lines. Drum lines sounded, and spectators gathered. I followed them down the road and saw more military personnel, signing songs in a band. An art exhibit displayed photos from the Vietnam War, celebrating Vietnamese strength and resistance in the face of American military bombardment. The photos depicted daily life in total war, and displays showed the bicycles that civilians used to deliver materials to the Viet Cong.

In the afternoon, I visited a Viet Cong themed cafe and tried “yogurt coffee.” I was skeptical about this combination at first, but it’s now my favorite coffee drink. It’s like the breakfast version of an all in one shampoo, you eat and drink coffee at the same time. And it’s delicious, of course.

Inspired to recreate these caffeinated beverages at home, I bought a Vietnamese coffee maker and have been using it at each hostel since Vietnam (I’m actually writing this blog from eSwatini).

I sent a message to my buddies from the airport, including a French Canadian named Dylan. He told me about a tour he was taking across Ninh Binh. I signed up to join him.

We explored ancient temples and climbed terraced mountains, bordered with sculpted stone dragons. On delicate boats, we floated through caves and between steep mountains. I wore a Vietnamese dress I had bought the day before, and got much positive attention from our tour guide and Vietnamese passerbys.

“Pretty lady! This dress suits you,” a coffee vendor exclaimed, and took a picture with me.

“I’ll teach you Vietnamese by the end of the tour,” our guide promised.

The Snakebite Heroes of Hanoi

I took a “Grab” bike (a motorcycle taxi through “Grab,” Southeast Asia’s Uber-like app with the green-jacketed drivers I had seen zipping around the old city) to the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology. I was there to Dr. Tao Nguyen Thien, Vietnam’s “snake whisperer,” and his team. Tao is a biologist by trade, but felt compelled to get involved in snakebite after seeing the public health toll caused by envenoming. His lab conducts ecological, public health, and venom research.

I spoke with Tao, and he elaborated on the local situation. While antivenom is fairly well distributed across Southern provinces, the North has been facing a more complex situation. Antivenom is much more difficult to come by, and many patients have to travel many hours on rough roads to reach hospitals with antivenom. At the same time, antivenom was made using venom from southern and central snakes. So, Northern snakes from the same species may have different venom (although more research needs to be done).

Vietnam produces only two antivenoms:

1.) SAV-Tri, covers Trimeresurus albolabris, the white lipped green pit viper.

2.) SAV-Naja, covers Naja kaouthia, the Monocled cobra.

Due to cross specificity, these antivenoms cover 4 of 7 of the Category 1 “highest medical importance” and 6 of Vietnam’s 9 category 2 venomous snakes. However, this means that there is no available antivenom to treat bites from four potentially deadly snakes.

Tao’s lab worked with the Institute of Vaccines and Medical Biologicals (IVAC) to produce two new antivenoms which would fill this gap, targeting Vietnamese Malayan pit viper and Kraits (B. fasciatus and B. multicinctus). The antivenom was ready, and showed great effectiveness in preclinical tests. During the COVID pandemic, however, health priorities shifted and the project was placed on an indefinite pause.

Only the Bach Mai, Cho Ray Hospital, and Ninh Thuang hospitals have ever stocked Thai antivenoms, and the second two hospitals may or may not have stock at any point of time. In any case, these antivenoms are expensive and difficult to obtain.

Vietnam has a thriving commercial snake market. Snake meat and snake wine are considered delicacies across much of East Asia. Besides their nutritional value (and as an “exotic food” which tourists pay high dollar for), snakes have medicinal properties in Eastern traditional medicine systems. Vietnamese snake farms supply non-venomous rat snakes, venomous monocled cobras and other snakes to domestic markets and the huge Chinese market. Certain villages, called “snake villages” specialize in snake farming.

Vietnamese law protects King cobras from capture, breeding or poaching, but these snakes are in high demand. There is evidence of a black market for King Cobras, with public health concerns:

For one, all snake farms place workers at risk of bites. Indeed, Tao’s epidemiological studies have shown relatively higher incidence of envenoming in snake villages. Bites are happening within the farms themselves, and impacts may spread beyond these industries; in the past, Monocled cobras weren’t distributed across Northern Vietnam. Now, however, they can be found across the region. Tao suspects that the snake meat industry could be partially to blame. Monocled cobra farmers who went out of business could have simply released their snakes, allowing them to reproduce in the wild.

To complicate matters, snakebite victims may be reluctant to report a bite from protected species such as the king cobra, since there could be legal repercussions. This is problematic, since King Cobra bites require specialized Thai monovalent antivenom, which is only available at certain aforementioned facilities. Medical professionals need to know which species bit the patient in order to treat appropriately.

Tao and his team work alongside medical professionals to ID which snakes could have bitten the patients, using photos and symptoms. Others are working on a diagnostic test to help ensure that victims receive the correct antivenom.

Lệ Mật Snake Village

I woke up oddly tired, but decided to visit one of these famed snake villages. I hopped on a motorcycle to Lệ Mật, and immediately began seeing “snake restaurant” signs everywhere. What better way to learn than participation? I walked in and took a seat.

The restaurant had a set menu; 6 snake dishes. Snake spring rolls, sticky rice with snake fat, snake stir fry, minced snake ribs, fried snake skin and snake meat wrapped in a leaf. They showed me a rat snake, calling it a bamboo snake, and bent its neck, slicing the poor thing and dripping its blood into a glass.

I felt like a monster. I sat, watching the slaughter of a beautiful animal that I had grown to love. But, I’m a meat eater, and all meat is killed. Cows are much smarter, and much cuter, but I don’t have to watch their slaughter every time I eat a burger. Anyways, this seemed like a pretty quick death. So, realizing that my horror is partially an effect of my cultural background and upbringing, I watched the process with fascination.

“We usually drink this. Do you want to drink it?” The waiter asked, handing me a shot glass with pink liquid: liquor and snake blood. I drank. The blood was imperceptible. He offered me the heart, but I couldn’t bear the idea of eating a raw heart from any animal.

The dishes came out quickly (almost suspiciously quickly; I think they had the food ready but do the slaughter for show). It was an impressive display. I took a video, admiring each dish and confirming what each was with the waiter.

“Yumyumyumyum,” said the waiter, catching me off guard as he “airplaned” a spoonful of sticky rice with minced snake meat into my mouth as if I were a toddler. The flavor was delicious. If I didn’t know any better, I would have thought it was pork (was it pork?). I nodded and threw a thumbs up to the waiter, who bowed and rushed off.

The spring rolls with fish sauce were savory and bright, as was the meat wrapped in leaves. The stir fry was the first meat that I could really tell it was snake-ey; the meat was tough and chewy, and I could see the round shape of the snake muscle which had been chopped through. The waiter brought a bottle of snake wine and another shot glass, included in the meal.

The fried snake skin scared me a bit. I could see the scaly pattern (although the scales had been scraped away). I lifted up a thin piece of the tail; there was the snake’s hemipenis, the male reproductive organ. It was chewy, but (with the chili sauce) zesty and fatty, like a particularly chewy bit of bacon.

Due to the wait time and flavor, I wonder whether it was all snake meat or some combination of snake and pork. In any case, I enjoyed the meal and experience. I was feeling some heavy fatigue, so I hoped that some of these traditional medicinal properties would pep me up.

I took a nap, then peeled myself out of bed to meet up with Dr. Tao’s team. His team and some other partners were celebrating Christmas Eve. They welcomed me warmly, and invited me to partake in the array of dried fish, marinated chicken, pomelo with chili powder, and sweet plum wine. We discussed culture, society, food and politics. I told them about my visit to Lệ Mật, and asked whether they had eaten snake.

“Of course. Many people in Vietnam have eaten snake,” one researcher replied with a smile.

Another researcher leaned over, whispering, “I have not eaten snake. It’s not my thing.”

One young scientist rushed from across the table and presented a video; it was him, bending the snake’s neck and cutting out its heart, as I had seen today.

“We do it at home usually,” he explained. “Did you eat the heart?”

I laughed, and admitted that I hadn’t been brave enough. The evening conversation was warm and pleasant, and we said merry goodbyes with plans to keep in touch and collaborate across borders.

The next day, I flew to Ho Chi Minh City and met Dr. Uyen Vy Doan, “Vanessa”. We discussed her past work.

Vanessa established the first poison control center in Southern Vietnam at Cho Ray Hospital. As you’ve seen in past blogs, other countries such as the US, Thailand, and India have poison control centers which specialize in the treatment of poisoning and envenoming, conduct important research, provide clinical consultation services and more.

In Vietnam, Vanessa explained, the “poison control center” concept is still a new and relatively unconventional idea. Most hospitals demonstrate no interest in maintaining such a center, since they generate very little revenue and don’t see the purpose. She fought hard to open the poison center at Cho Ray, and kept it running for almost a decade (in the face of many obstacles) before she decided to leave. The center has shut down in her absence, but she hopes to teach students about toxicology and establish a foundation for future improvements in the country’s management of poisoning.

We spent the rest of the evening together, trying central and southern Vietnamese delicacies. All Southeast Asian food is amazing, but Vietnamese food is especially fresh and light, full of flavor and greens.

A few weeks after leaving Vietnam, I spoke to Bao Truong, a researcher who is working to improve understanding of the public health issue of snakebite. Unlike neighboring countries such as Thailand, Taiwan or India, Vietnam doesn’t have a separate system to report snakebites. Rather, these are recorded as animal bites. The patchy data only adds to the neglect. Vietnam still has national guidelines for the clinical management of snakebite, many victims still end up paying costs out of pocket, and many seek traditional healing rather than heading to hospitals.

Want to learn more? Check out these links!

Vietnam's leading expert on venomous snakes (About Dr. Nguyen Thien Tao)

Situation of snakebite, antivenom market and access to antivenoms in ASEAN countries

Wow. What an amazing read! Love your style.

(Not so) fun fact: I fell sick with Influenza A and pneumonia after this trip, which explains why I was so tired... But I got some juice, antivirals and antibiotics once back in India, and recovered quickly.