A rude arrival…

My bus arrived to Johannesburg later than originally planned. When we arrived, it was already dark. I called an uber, and waited outside. The other bus passengers slowly got picked up, and I waited in the dark. Finally, my car pulled up, closely tailed by a yellow city taxi. The taxi parked right behind the car, and when the car driver opened the trunk, the taxi driver began to aggressively get out of his vehicle. My car driver anxiously looked toward the taxi driver, looked at me, then slammed the trunk and sped off. The taxi driver inched back a few feet and waited in front of me in the dark. Something was really off…

I began walking away from the taxi driver, going to find a well lit area. A group of South Africans caught up with me.

“Hey, are you okay? Do you need us to wait with you until you get your ride?” They asked, explaining that they were a group of friends visiting from Cape Town.

“No, it’s oka…. Actually, yes please,” I responded gratefully. We walked toward the light and I ordered another Uber. He was one street away, but wouldn’t move. Afraid to leave the light, I called and texted.

“Come here,” was his response. Finally, the cape towners and I walked over to the street and found my new driver. As we drove toward my hotel, I told him what had happened.

“That’s why I didn’t want to come. That’s taxi territory. They sometimes burn cars or attack over drivers for coming there,” he explained nonchalantly. “Welcome to Joburg.”

Stunned, I sat thanking God that nothing had happened. I checked into my hotel, ate some dry rusks for dinner, and slept.

The man, the myth, the legend: African Reptiles and Venoms

The next morning, I headed to meet Mike Perry at his house/ serpentarium. At this point, I had met multiple of his mentees. It was exciting to meet Mike, who had trained and inspired so many snake experts and snakebite advocates. A tall and gruff, but kind man, Mike shook my hand and had me sign some paperwork. He took me through a series of long, thin buildings. Snake cages were stacked floor to ceiling, holding colorful and alert specimens from across the continent.

Mike casually slid out box after box, showing me baby puff adders and elegant boomslangs. In smaller, transparent boxes, minuscule black-necked spitting cobras and zebra cobras wiggled, watching us as we watched them. Mike made comments about each one as if they were his children. After touring the building, we made our way to his office, where he showed me vials of freeze dried venom. I marveled at the huge quantity.

“These shipments were supposed to go to SAVP for antivenom production, but they’re doing renovations right now. They even sent these venoms back,” Mike said. “Who knows when they’ll start up again…”

Even in good times, Mike explained, venom production is not profitable. He remains in the business at a loss, because he loves snakes and has built his life around these creatures. He used to make ends meet by giving snake handling courses, but more and more snake handlers have begun to offer courses. Meanwhile, family situations have made it so that Mike can’t leave home for the time being.

I reflected on how many people in various African countries that had told me about their ideas to start a snake farm and produce venom in hopes of making a quick buck. If they saw what I had seen, they would likely reconsider these plans.

Mike and his coworker, Zenobia Van Vuuren, showed me some of the snake handling equipment they sell. Gloves, hooks, tubes, bins, shin protectors, and more, all with the African Reptiles and Venom logo. Zenobia showed me their antivenom stocks and their filing cabinet full of clinical snakebite cases. They hoped to make a book on snakebites to help clinicians and experts better understand the impact of African snake venoms.

It only gets snake-ier

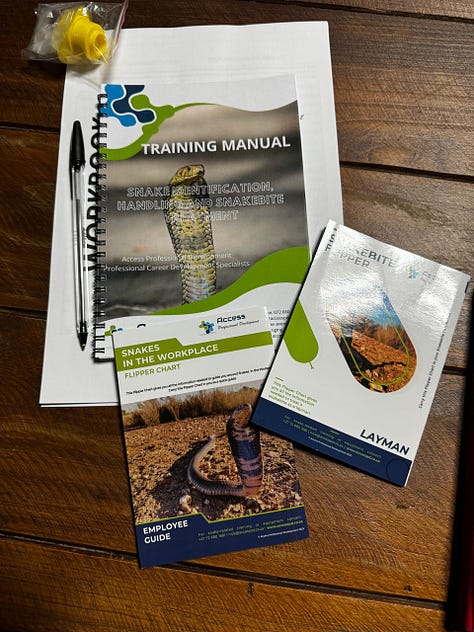

The next day, I took a taxi south toward Vereeniging to meet Nick Van Der Walt, an EMT, snake handler and new friend I had met at the eSwatini antivenom conference a week ago. Nick teaches snake safety courses for corporations and agencies who are exposed to snakebite risks. Since South African law requires employers to take steps to protect workers, they pay for one-day training courses on snake identification, snakebite prevention and first aid. Nick invited me to attend a workshop with the South African wildlife department.

We all sipped coffee, listening intently as Nick described South African snake species and their distributions, symptoms of envenoming, venom potency and fun facts. He walked us through the basics of how venom works, with diagrams, stories and clinical photos. After a lunch break (South African mutton curry with mashed potatoes— super yummy!), we stepped outside for some hands on practice. We took turns lifting a chunky puff adder with two hooks, scooping up a cobra tail and guiding cobras into a pipe, and moving the puff adder into the bin. By the end of the day, everyone had practiced safely moving a venomous snake. We pocketed our handy flipbooks, which Nick had designed for reference in case of a snake spotting or a bite. We then took a test on our new snake safety knowledge before saying our farewells and heading home. Nick and his colleague drove me back to Johannesburg, telling me stories about their trips to remote regions across Africa for snake handling trainings.

Durban: Guidelines and Geckos

The next day at 4am, I caught a flight to Durban, a city on the southern cost of SA. There, upon landing, I grabbed my bag and headed straight to the Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital to meet Dr. Timothy Hardcastle, a medical doctor and snakebite expert. Dr. Hardcastle explained the history behind South Africa’s snakebite initiatives. It all began as a group of snake experts, and evolved into a robust network that collaborates on activities such as education programs, the creation of national guidelines on the treatment of snakebite patients. Dr. Hardcastle spearheads much of the clinical side, continuing to conduct trainings for clinical professionals.

After meeting Dr. Hardcastle, I sped back to my hotel and presented a talk on my findings from Kenya. I discussed clinician knowledge, antivenom access and efforts to combat snakebite (topics I’ve spoken about in the last 2 blogs). Participants from Nigeria, the UK, India, Thailand, and the US discussed the Kenyan snakebite situation, sharing and comparing their own experiences. After the call ended, Kenyan colleagues called me to congratulate, expressing satisfaction with the review and the international audience. It was a beautiful moment, where I felt like I could share a little bit of my “Watson experience” with others.

I spent the following two days in Durban. I explored the city, learning some Zulu words from the Airbnb hosts and visiting a reptile center, “Dangerous Creatures”. The reptile center was Nick’s recommendation, and it didn’t disappoint; I spent almost two hours observing the snakes in their lunch enclosures. I looked at their pupils, trying to guess whether they were diurnal or nocturnal. I compared their scales (smooth, “keeled”, bumpy), their head shape, their colors, patterns and behavior (are they chilling on branches? On the ground? In the water?).

I found myself recognizing some snake species and families from India, Africa and Thailand. It was an exciting moment for me, as I reflected on my first Watson days in India where I couldn’t tell a python apart from a viper or cobra. I was staring at the black mamba when something grazed my ankle. Adrenaline shot through my body and I jumped, looking around the ground as I continued my “high knees”.

The floor was empty.

Hiss, click!

From a slit on the bottom of the wall in front of the enclosure, a little wire flew out, flying through the area I had been standing, and slid back into its hole. It was a little prank.

A staff member giggled from behind me.

“In front of the mamba enclosure?! That’s just cruel,” I laughed.

We joked together for a while, exchanging fun facts about reptiles and snakebites.

Toward the end of my slow perusal through the enclosure, a voice asked me, “Do you keep snakes?” I spun around to find a uniformed man. “Normally people walk through in about 15-20 minutes.”

I had been there for well over an hour at this point. Feeling a bit bashful, I responded. “No, I don’t keep any snakes. But, I study snakebites, so I find snakes fascinating.”

The man, Carl, smiled kindly, asking me where I was from, suggesting local snakebite contacts and introducing me to another colleague (Craig) who keeps up with the snakebite world. Carl (who I found out was the owner), invited me downstairs to see the babies and animals that weren’t on display. Thoroughly delighted, I held tiny, vibrant green pythons and an angry (but toothless) egg eater snake. We watched as the egg eater curled itself into a “U” shape, mimicking the defensive behavior of the highly venomous Echis carpet vipers.

“This guy pretends to strike when he feels threatened, but he will always miss. Watch this.” Craig said, waving his hand in front of the little snake. The egg eater rubbed its scales and lunged forward. Each time, its little head narrowly missed Craig’s hand.

I held a soft but leathery gecko, mesmerized by its strange little feet. The pads were covered in tiny flaps of skin, which somehow stick to glass despite being dry.

“It’s feeding time for the vine snakes,” Carl said. “Are you bothered by feeding?”

I shook my head, no. My first exposure to snakes was at the Instituto Clodomiro Picado, where I hung out with the herpetologists and filmed the feeding. While it’s sad to see the little rodents lose their lives, most reptile keepers kill the animals beforehand (using CO2 or breaking their neck) so that they don’t suffer as much. It’s part of the circle of life, and my presence doesn’t change the reality that these animals need to eat! With a long pair of tweezers, he grabbed the limp baby mouse and waved it in front of a vine snake, a highly venomous rear-fanged snake.

Despite being deadly, there is no antivenom to treat vine snake bites. Their venom causes severe haemorhage, but very few accidents happen with vine snakes. They’re passive (see: chill) snakes that tend to only bite when people are trying to handle them. Since so few cases happen per year, no companies have included vine snake venom in their recipes.

The snake snapped up the baby mouse (called a pinky, because they’re hairless and pink).

“Want to try?” Carl asked.

I grabbed the long pincers and approached the open cage where a second vine snake lounged on a twig. I waved the pinky in front of its face. The snake sat motionless.

“You might want to wiggle it a bit.”

I wiggled the pinky. Then, SNAP! The vine snake grabbed hold. I released the mouse with my pincers and backed away from the cage. Awesome.

Back in Johannesburg, ubered out of the city to meet Jason Seale, a reptile park owner and antivenom aficionado. As an exotic snake owner, Jason has kept up with antivenom companies from across the world. We sat at a table for hours, discussing the current situation with SAVP and antivenom access. We compared notes.

South African Vaccine Producers, SAVP, has halted antivenom production. I’ve heard various explanations as to why:

Updates to lab facilities and equipment

Electricity shortages and rolling blackouts

Breakout of horse disease

Underfed horses

WHO disapproval of current facilities

SAVP has affirmed that it hopes to restart in a few months, but it’s hard to know whether that timeline will be followed. Meanwhile, South Africa has stock-outs across the country.

“Other antivenoms are available in South Africa,” Jason explained. “But they are available under a South African pharmaceutical regulation called ‘Section 21’. This is an emergency import. Under section 21, it’s forbidden to market antivenoms. This means that a lot of physicians in snakebite prone regions don’t realize that antivenoms are available.”

After much chatting about venoms and antivenoms, I headed back to Johannesburg. Following these visits, I’ve been reflecting a great deal on the issue of knowledge and awareness. In South Africa, the solutions are there; clinical guidelines exist, and antivenom is available. But, getting the information to the people who need it most is often the largest hurdle.

Want to learn more? Check out these links!

Access Professional Development

Approach to the diagnosis and management of snakebite envenomation in South Africa in humans